Photo: Sebastià Torrens. Question marks: Aina Bonner

Photo: Sebastià Torrens. Question marks: Aina Bonner

Solution to Challenge 3

The study of lethargy in birds began in the 1950s. It is now known to be more widespread than originally thought. Birds are homeothermic vertebrates, with a “constant” temperature.

Normally the body temperature of birds at rest is around 38º C, and it can rise a little when they are active. In some birds when they are active it rises to 41º C, and in some can even exceed 43º C. Then we speak of hyperthermia. Hyperthermia does not produce lethargy, but rather involves thermal regulation problems to maintain the body temperature below ambient temperature. It’s another problem.

Normally, at night in cold climates, the birds’ body temperature may drop a few degrees, but the birds are “wake” by responding to external stimuli. These small drops in body temperature are very frequent, they are widespread among birds, they are “normal”. When the dropping in body temperature exceeds 5º C, we begin to speak of hypothermia, while if this threshold is not exceeded, we speak of normothermia. It is a proposed convention, but not accepted by everybody.

The forms of hypothermia can be classified into three categories: (1) resting-phase hypothermia; (2) lethargy; and (3) hibernation.

Resting phase hypothermia is a temperature drop of a few degrees. Birds that fall into this type of hypothermia maintain their attention, move -more slowly than when they are normothermic- and can fly. This type of hypothermia is thought to be widespread among birds, but it is not well studied. Some examples of species that can fall into this type of hypothermia are, among the species that are best known to us, the Griffon (Gyps fulvus), the Great Tit (Parus major), some swallows,…

There are birds that have extremely high energy requirements, that depend on high-energy foods (for example, nectar, insects) and that are not always available. These birds have found a way to minimize their energy expenditure during the hours of the day when they cannot get the fuel they need. To save energy, these birds have evolved by greatly reducing the metabolic expenditure necessary to maintain their constant temperature, until reaching a state of lethargy. When they fall into this state they are often totally immobile and do not respond quickly to external stimuli. Their body temperature drops below 22º, and almost all above 15º (although some drops to 6º C). Among the birds, all the hummingbirds (Trochiliformes) that have been studied fall into torpor every day, during the night (some species that live in the Andes mountains, also sometimes during daylight hours). Also the Apodiformes (swifts) and Caprimulgiformes (nightjars) have species that can occasionally fall into torpor. Also, the African mouse-birds (Coliiformes) and among the Coraciiformes, the genus Todus, the precious todies of the Antilles.

Hibernation is the third category of hypothermia. Hibernation differs from torpor in a couple of ways. Like torpor, it is a state in which the species that have it when they have it are totally immobile and do not respond to external stimuli. Well, they do respond, but they take a lot longer to recover than do birds that fall into torpor. In addition, another difference is that the duration of hibernation is much longer (it can be days) than that of torpor (which is hours at most). The circadian rhythm is maintained in birds with torpor, but it is not maintained with hibernation. It is as if the biological clock has stopped almost completely.

For now, only one hibernating bird is known. This is the Nutall Nightjar from the Sonoran Desert, Phalaenoptellus nutalli. It is the only bird that has been clearly seen hibernating.

Nuttall Nighjar, Phalaenoptellus nuttallii. Source: https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Phalaenoptilus_nuttallii/

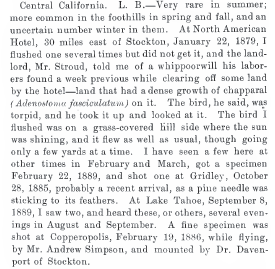

Hibernation was first suggested by Jaeger (1949), although some (few) specimens had been found that must have been hibernating many years earlier. The oldest record published in a scientific journal dates from 1890 and relates a finding of a specimen in January 1879 that must have been probably hibernating, as follows from its description.

In this volume, hibernating Nutall Nighjars are reported by Belding (1890):

Source: Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL)

During its hibernation the body temperature can drop to 3º C. Yes, three degrees. During the three winter months, some specimens are in this state 72% of nights, and can hibernate for up to 164 hours in a row. One specimen was also recorded that was inactive for 45 days (although it reactivated spontaneously by re-heating 8 times during this time).

This Nightjar lives in a desert. It is very small in size (35 g) and lays white eggs (unlike other Nightjars). Hibernates in “burrows” usually located at the base of cacti of the genus Opuntia. In 2004, a study suggested that other species of desert Nightjars might be hibernating: Caprimulgus tristigma (South Africa), Caprimulgus longirostris (South America), and Eurostopodus argus (Australia). These candidates have not yet been studied well enough to be able to ascertain whether or not they hibernate.

References

Bahat, O. i Choshniak, I. 1998. Nocturnal variation in body temperature of Griffon vultures. Condor, 100: 168-171.

Belding, L. 1890. Land birds of the Pacific district. Occ. Pap. California Acad. Sci., 2: 1-274.

Brigham, A., McKechnie, A.E., Doucette, L.I. i Geiser, F. 2012. Heterothermy in Caprimulgid Birds: A Review of Inter- and Intraspecific Variation in Free-Ranging Populations. In Ruf, T. et al. (eds), Living in a seasonal world: 175-187.

Culbertson, A.E. 1946. Occurrences of poor-wills in the Sierran foothills in winter. Condor, 48: 158–159.

Howell, T.R. i Bartholomew, G.A. 1959. Further experiments on torpidity in the Poor-will. Condor, 61: 180-185.

Jaeger, E.C. 1948. Does the poor-will “hibernate”? Condor, 50: 45–46.

Jaeger, E.C. 1949. Further observations on the hibernation of the poor-will. Condor, 51: 105–109.

McKechnie, A.E., Ashdown, R.M.A., Christian, M.B. i Brigham, R.M. 2007. Torpor in an African caprimulgid, the freckled nightjar Caprimulgus tristigma. J.Avian Biol., 38: 261-266.

McKechnie, A. E. i Lovegrove, B. G. 2002. Avian facultative hypothermic responses: a review. Condor, 104: 705–724.

McKechnie, A. E. i Mzilikazi, N. 2011. Heterothermy in afrotropical mammals and birds: a review. Integrative and Comparative Biology 51, 349–363.

Nilsson, J.-Å., Molokwu, M.N. i Olsson, O.2016. Body Temperature Regulation in Hot Environments. PLoS ONE, 11, 8: e0161481.

Ruf, T. i Geiser, F. 2015. Daily torpor and hibernation in birds and mammals. Biol.Rev., 90: 891-926

Schleuser, E. 2004. Torpor in Birds: Taxonomy, Energetics, and Ecology. Physiological and Biochemical Zoology, 77, 6: 942–949.

Withers, P. C. 1977. Respiration, metabolism, and heat exchange of euthermic and torpid poorwills and hummingbirds. Physiological Zoology, 50: 43–52.

Woods, C.P. i Brigham, R.M. 2004. The Avian Enigma: ‘‘Hibernation’’ by Common Poorwills (Phalaenoptilus nuttallii). In Barnes, B.M. i Carey, H.V. (eds.), Life in the Cold V: Evolution, Mechanism, Adaptation, and Application. 12th International Hibernation Symposium. Biological Papers of the University of Alaska, number 272 :31–240.

Woods, C.P., Czenze, Z.J. i Brigham, R.M. 2019. The avian “hibernation” enigma: thermoregulatory patterns and roost choice of the common poorwill. Oecologia, 189: 47–53.